Sorry to Burst your Bubble!

A Look at the Behaviour of Past Bubbles and Current Reality

Bubbles are fuelled by bias. Here I unpick the behavioural pitfalls that tend to lead to extreme investor herding behaviour and compare this to the trends in the market today. My analysis aims to provide educational insights into market behaviour and historical trends and does not offer specific investment advice.

Last year was one of the narrowest market rallies on record. The Magnificent Seven dominated stock market performance and it was difficult to outperform the MSCI ACWI index if you were under-weight these names. As valuations rise, investors and market analysts are increasingly worried a megacap bubble is forming.

Investors tend to overweight superficially similar past events when making forecasts about the future. Traumatic past events serve as particularly emotive anchor points. Anchoring is a particularly insidious heuristic that reflects our tendency to anchor our expectations to reference points, often insufficiently adjusting for differences. Today, the trauma of the internet bubble of the 1990s and the Nifty Fifty of the 1970s are being frequently referenced as cautionary tales. In situations like this it is worth unpicking whether these are helpful reference points or not, and what can be learnt from the past.

Many famous bubbles have been well documented over the past four centuries, from Holland's tulip mania in the 1630s to the 2008 housing crisis. Edward Chancellor traces the origins of this speculative spirit in his engaging book ‘Devil Take the Hindmost’, revealing how little we actually learn from the past. What is striking is that, despite representation across vastly different industries and circumstances, common patterns of irrationality underpin these events, offering important lessons to investors today.

*

First is remarkable price appreciation in a relatively short period of time, often fuelled by excitement and speculation.

Since the financial crisis, a steadily increasing share of the S&P500’s return has come from the five biggest stocks in the market. Last year 39% of the market’s return came from the top five stocks. Nvidia appreciated a remarkable 244% over this period. While unusual (and uncomfortable) I would argue this price appreciation is not overtly speculative.

Magnificent growth used to require investors to sacrifice current profitability for future prospects. Today’s crew (excluding Amazon and Tesla) subvert this trend, throwing off enormous amounts of free cash flow that provides optionality on exciting new technologies.

This is challenging for analysts to forecast because (1) new markets and business models lack good anchor points for expectations, and (2) change and compounding growth jar with forecast models that linearly extrapolate from the past and commonly over-forecast mean-reversion. The result is sticky under-reaction to better-than-expected news.

Investors are more trusting of the cash flow story now but don’t seem excessively optimistic. Valuation differentials aren’t too far above historic averages. That doesn’t mean the stocks look outright cheap, but valuations don’t look too out of sync with fundamentals.

However, it's worth considering where we are in the technology cycle. AI is still in its infancy and is mainly being used to automate existing workflows. The pace of innovation is hectic and prone to confidence-dropping errors.

It is unclear if/when these early use cases will explode in general usage. While the internet began to be used in the early 1990s, it was not until the late 2000s that two-thirds of US businesses had a website. Building out the infrastructure to replace outdated systems can be costly, complicated and painful. With AI there are also challenging ethical questions to navigate.

It is also unclear when new use cases will appear and expand. Early innovation cycles are typically characterised by surges and troughs in demand as further conceptual leaps forward are limited by the need to navigate new performance ceilings. These ups and downs are almost impossible to predict, driving investor sentiment in mini-cycles of excessive optimism and gloom.

Nonetheless, resource intensity seems set to increase along this lumpy path, disproportionately benefitting a handful of large platforms with the capital, talent, and data required to navigate this unpredictability.

*

Second, bubble mania is often underpinned by a belief that something big has changed.

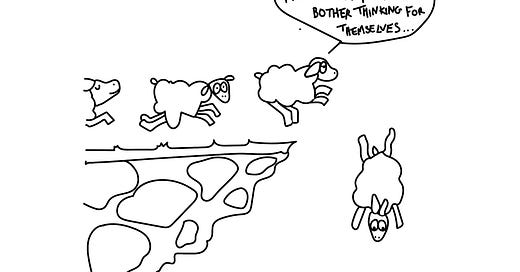

This tends to be related to new, apparently disruptive technologies. An exciting story is a powerful motivator of investor herding, and such speculation is often strongest at the start of a new industry.

Extreme speculation commonly draws in multiple asset classes, sectors, and investors. During the early internet boom of the 90s, a company that added 'dot com' to its name could add multiples to its valuation even if it had nothing to do with the internet. In Britain during the 1840s, railways were considered a 'sure bet', attracting a breadth of investors from the Brontë sisters to Sir Isaac Newton.

Higher valuations are often justified with biased arguments (e.g. 'You can’t get fired for buying IBM’). The current hype surrounding AI is notable, but arguably contained. The blind optimism seen last year in the prospects of AI has been replaced by a reasonable dose of scepticism, driving a wide divergence between the share prices of the large US tech companies this year. While many companies today are ambitiously declaring themselves to be 'AI-enabled' in one way or another, investors seem to be discriminating between those where claims are backed up by fundamentals and those where they are not. Perhaps the internet bubble of the 90s has been a helpful lesson?

*

Third, lax or loosening regulation often contributes to financial bubbles by increasing a company's risk appetite. For example, light touch regulation of financial institutions was an important factor in the excesses that led to the 2008 housing bubble.

Today the technology megacaps face a tough regulatory environment. There is building scrutiny over their monopoly-like profits and positions as gatekeepers for many new technologies. Regulation is a double-edged sword. While it can help constrain excessive risk-taking from CEOs, it can also blunt a company's ability to expand into new revenue streams. This bears monitoring but for reasons exactly counter to bubble formation.

The large platforms are difficult to regulate in their current form as they are not price gouging. They play a critical role in making infrastructure more accessible and affordable, enabling parts of the technology ecosystem to proliferate. If the federal government did act to break up some of the big tech, that is not necessarily a negative for the shareholders in the long term. It could lead to leaner and more focused companies that outperform. However, the looming presence of the regulator creates a sense of existential angst among investors, which could help prevent rational optimism from tipping into irrational exuberance.

*

Fourth, many bubbles are fuelled by easy money. This was a hallmark of the dot com bubble where record amounts of capital flowed into the Nasdaq. By contrast, today's credit lending environment is challenging. The long period of low interest rates that preceded the pandemic has ended and has been replaced by a healthy scepticism towards growth at the expense of profits.

*

In sum, the differences between conditions today and the pattern of past bubbles seem to outweigh the similarities. Market leadership is narrow, driven by stocks that are clearly benefitting shifting customer preferences today or are setting themselves up to benefit soon. Valuations don’t appear too out of kilter with very strong fundamentals. The regulatory environment and capital flows are getting tighter, not looser, constraining the ability of CEOs to take excessive risk. These are not hallmarks of a bubble. However, the nature of the technology and regulatory cycle means the path for some of these AI-exposed companies will likely experience mini-cycles of surprise and disappointment by dint of being difficult to predict. I suspect investors in some of these large AI beneficiaries will be in for a bumpy ride.

*

In Does Scale Matter? I take a look at the shape of surprise in today’s market and what this may tell us about how things may play out going forward.

Disclaimers:

This blog post is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, financial advice, or any other type of advice. The information contained herein is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice, including but not limited to investment or financial advice. The content presented in this blog post reflects the personal views and opinions of the authors at The Heuristik Blog and it may not necessarily represent the views of any other individual or entity.

Investing in financial markets involves risk, including the risk of loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Before making any investment decisions, it is important to conduct thorough research and consider seeking advice from a qualified professional, such as a licensed financial advisor or investment manager.

The Heuristik Blog is not a registered investment advisor, broker-dealer, or financial institution. We do not endorse or recommend any specific investment products, services, or strategies.

Readers are encouraged to exercise caution and discretion when implementing any information or strategies discussed in this blog post. We disclaim any liability for any loss or damage resulting directly or indirectly from the use of or reliance on the information presented herein.

By accessing this blog post, you acknowledge and agree that The Heuristik Blog shall not be held liable for any damages or losses arising from your use of or reliance on the information presented herein.

Copyright © 2024 Emilia Beck-Friis. All rights reserved.

For any further enquiries:

E.beckfriis@heuristikcapital.com